From Reactive To Proactive

David Boyle looks at the thinking behind the National Inquiry into Universal Healthcare.

THE whole idea of the NHS is that it has to be fair. Everyone in the NHS is bending over backwards to make the services accessible to all who need them.

Given this, the problem is that nobody agrees about why people’s health is so much worse when they are poorer. The team behind the National Inquiry from London South Bank University (LSBU) have been, very quietly, working away on how the NHS works with Integrated Care Systems in Bradford District and Cravenand Sussex.

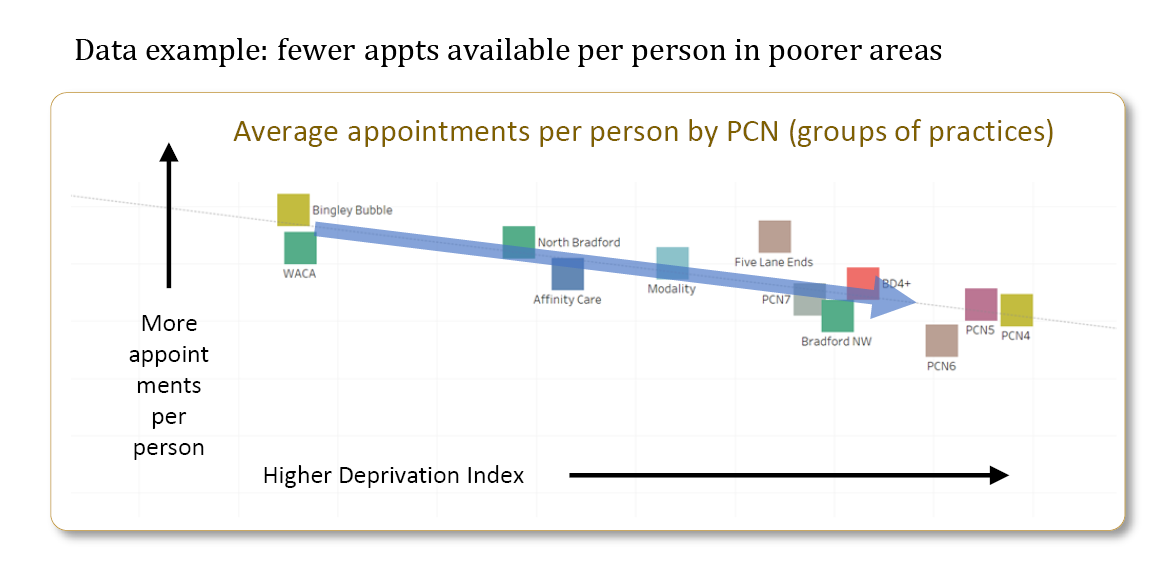

What they found is that it isn’t just a matter of there not being enough money – the roots of the problem are very local indeed. The key issue is that treating everyone the same way sounds fair – but, as they have found, actually isn’t.

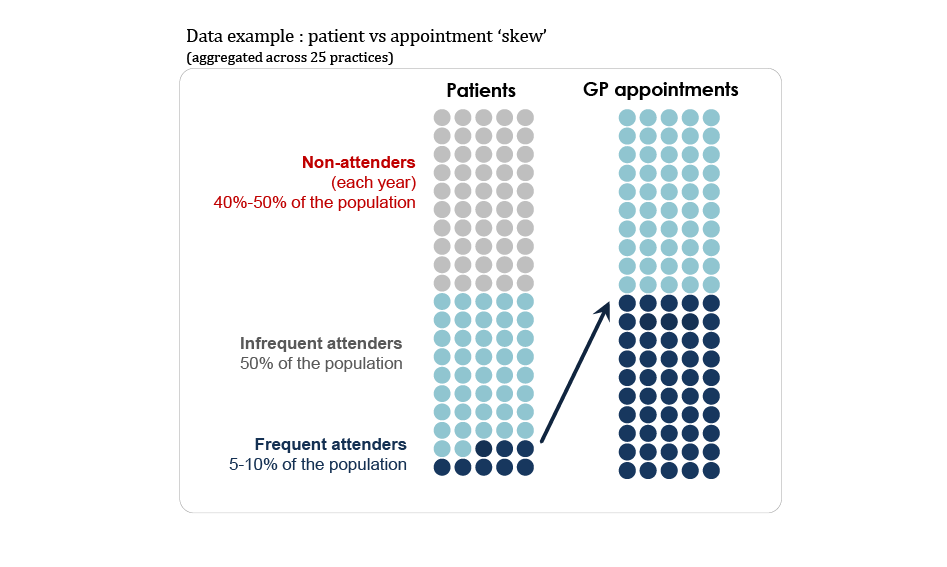

“What we have found is that not everyone will get what they need,” says Professor Becky Malby, the inquiry leader, “because everyone isn’t the same.” When you have a one-size-fits-all service, the only ones who are able to access it are those whom the one size suits. People with flexibility get what they need, but those with less flexibility – because of financial or other circumstances – get left out.

During the pandemic, we had to work very differently - involving the voluntary sector, local charities and thousands of local volunteers – to take the vaccine out to where people were, and to make sure it reached them. “We simply have to move our operation closer to where people are,” says Bradford District and Craven participant Bill Graham.

Why has it been so ineffective? They believe there are three broad reasons:

1. Already stretched NHS infrastructure is expected to tackle people’s deep-rooted problems, like poverty – or maybe poverty itself damages people’s health. GPs want to help, but maybe the reason they are getting such an increase in patients is because patients don’t know where else to go. The question is how can we work with other local organisations so that they can support people in poverty, rather than relying on GPs using sticking plasters to cover up symptoms.

2. People are not ‘hard to reach’- but they are easy to miss. We need to redesign services that work for local people.

3. The NHS is failing some groups in particular. For example, children and young people don’t tend to access services even though they are suffering from worse mental health since the pandemic.

Professor Malby said: “We have been working to find out why this is and what we can do about it. With stretched health resources at the moment, we need to make sure that everyone can access medicine and care - and that means re-designing services to give everyone an equal chance. It means shifting from reactive healthcare – which sits back and waits for whoever comes through the door - to proactive care – which means going out into the community and working with the voluntary sector there.

“WE KNEW that the most important thing was to start, to get going,” said Becky Malby. “From there, the road takes surprising turns as the system reacts to what is happening and everyone gets involved. This is a good thing as it brings new ideas, new people, and new solutions.”

THESE are some of Becky’s lessons on how to do this locally:

“The one thing that ‘holds’ the NHS in the mode to innovate and address these issues is having the community as partners in the inquiry and solution finding. Starting matters – local people have to be involved from the outset.

“Systems leadership is key, paying attention to the emerging ideas and solutions, and supporting people testing these out. People in the ‘middle’ are not confident in leading change without this support.

“Be non-judgmental and honest about the relationships in our system and inquire together about how things are now. Check your assumptions are based on evidence. Welcome people into the work.”